09: Assembly and MIPS

May 26, 2021

This article is a part of a series where I go through teachyourselfcs. If you would like to start at the beginning start here.

LECTURES

L5

Assembly language below high level language (MIPS)

Assebler turns assembly code into machine code

job of cpu: execute lost of instructions (primitive operations that the cpu can execute)

Example instruction set architectures:

- ARM

- x86

- mips

- risc-v

- ibm/motorola powerPC

- intel IA64

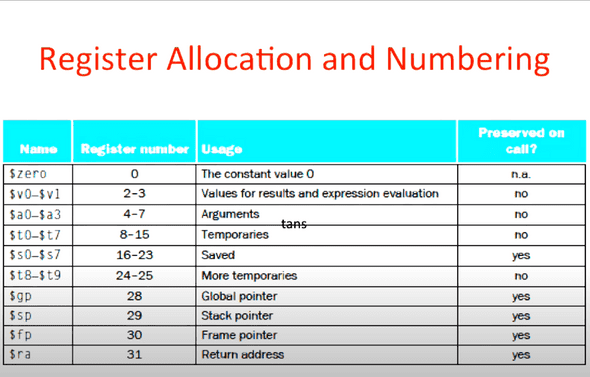

Assembly Variables: Registers

since registers are in hardware there is a limited number, 32 registers in MIPS

32 bits in a register, groups of 32 bits called a word in mips.

Number refererences: ($0, $1, $2)

or

name references: ($s0-$s7, $t0-\$t7) c variables and temporary variables (preffered because easier to debug)

add in assembly

add $s0, $s1, $s2 = a = b + c

subtract in assembly

sub $s3, $s4, $s5 = d = e - f

how to do a = b + c + d - e

add $t0, $s1, $s2 # temp = b + c

add $t0, $t0, $s3 # temp = temp + d

sub $s0, $t0, $s4 # a = temp - eImmediates:

Immediates are numerical constants, they appear often in code, so there are special instructions for them.

addi $s0, $s1, -10 #mips

f = g - 10 #cyou have a special register for zero cases

add $s0, $s1, $zero #mips

f = g #cOverflow handling in mips:

Detect overflow:

- add

- add immediate

- subtract

do not detect overflow:

- add unsigned

- add immediate unsigned

- subtract unsigned

only 32 registers, if you dont have space in registers you have to go to memory.

transfer from memory to register:

C code:

int A[100];

g = h + A[3];mips:

lw = load word

lw $t0, 12 ($s3) #Temp reg $t0 gets A[3]

add $s1, $s2, $t0 # g = h + A[3]s3 is a pointer to the beginning of the A array

offset is 12 (offset is in bytes) so it fast fowards 12 bytes in array or 96 bits 96/32 = 3 (32 is size of int) , have to increment base by the size of the datatype.

transfer from register to memory:

C code:

int A[100];

A[10] = h + A[3];mips: sw = store word

lw $t0, 12 ($s3) #Temp reg $t0 gets A[3]

add $t0, $s2, $t0 # temp reg $t0 gets h + A[3]

sw $t0, 40 ($s3) # A[10] = h + A[3]In addition to word data transfers mips has byte data transfers:

-load byte: lb -store byte: sb

same format as lw, sw

lbu for unsigned.

speed of registers vs. memory

smaller is faster with registers. registers are 100-500 times faster than memory.

mips if statement:

beq register1, register2, L1means: go to statement L1 if value in register1 == value in register2

otherwise got to next statement

beq = branch if equal

branch - change of control flow

conditional branch - change control flow depending on outcome of comparison

branch if equal (beq) or branch if not equal (bne)

unconditional branch - always branch

jump (j)

L6

Machine code is lowest level of software.

words and vocabulary are called instructions and instruction sets respectively

mips is example RISC instruction set

rigid format 1 operation, 2 operands, 1 destination

example operations:

- add

- sub

- mul

- div

- and

- or

- sll

- srl

- sra

operations to move data around registers and memory:

- lw

- sw

- lb

- sb

operations for decision/ flow control:

- beq

- bne

- j

- slt

- slti

program is stored as a bunch of bytes

mips instruction 32 bits or 4 bytes

Assembler converts assembly to machine code.

assembly code has .S extension machine code object has .o extension

machine code executable file has a .out extension

if a branch is false you go to next instruction else you jump to the given instruction (conditional branch).

unconditional branch: Always go to the “label”

C code

if (i == j)

f = g + h;mips code

bne $s3, $s4, Exit # notice this is not equal, if false this goes to next line which is add

add $s0, $s1, $s2C code

if (i == j)

f = g + h;

else

f = g - h;mips code

bne $s3, $s4, Else

add $s0, $s1, $s2

j Exit

Else: sub $s0, $s1, $s2

Exit:The jump is needed to jump over the else code, and go to whatever the next line of code is.

interpreted: compiled at run time, so as a line of code is being executed it compiles to assembly.

C code

if (g < h)

goto Less;mips code

slt $t0, $s0, $s1

bne $t0, $zero, Lessslt = set on less than

set means change to 1.

reset means change to 0.

sltu = treats registers as unsigned

slti = immediates

Six Fundamental Steps in Calling a Function:

- Put parameters in a place where function can access them

- Transfer control to function

- Acquire (local) storage resources needed for function

- Perform desired task of the function

- Put result value in a place where calling code can access it and restore any registers you used

- Return control to point of origin since a function can be called from several points in a program.

Function call conventions

- Registers faster than memory, so use them

- $a0 - $a3: four argument registers to pass parameters

- $v0-$v1: two value registers to return values

- $ra: one return address register to return to the point of origin

C code

int sum (int x, int y) {

return x + y;

}mips code

address (shown in decimal)

1000 add $a0, $s0, $zero # x = a

1004 add $a1, $s1, $zero # y = b

1008 addi $ra, $zero, 1016 # $ra = 1016

1012 j sum # jump to sum

2000 sum: add $v0, $a0, $a1

2004 jr $ra #new instructionjal = jump and link

laj = link and jump

link = form an address or link that points to calling site to allow function to return to proper address.

jr = jump register

$sp = stack pointer

Where are old register values saved to restore them after function call?

ideally they are in the stack.

push: placing data onto stack

pop: removing data from stack

stack in memory so need register to point to it ($sp register 29 in mips)

when adding $sp decrements to add more space

when removing $sp increases to decrease space.

C code

int leaf_example (int g, int h, int i, int j)

{

int f;

f = (g + h) - (i + j);

return f;

}paramerter variables g,h,i,j in $a0, $a1, $a2, $a3

f in $s0

1 temp register $t0

mips code

addi $sp, $sp, -8 # adjust stack for 2 items

sw $t0, 4($sp) # save $t0

sw $s0, 0($sp) # save $s0

add $s0, $a0, $a1 # f = g + h

add $t0, $a2, $a3 # t0 = i + j

sub $v0, $s0, $t0 # return value (g+h)-(i+j)

lw $s0, 0($sp) # restore register $s0 for caller

lw $t0, 4($sp) # restore register $t0 for caller

addi $sp, $sp, 8 # adjust stack to delete 2 items

jr $ra #jump back to calling routineWhat if function calls another function?

have to save the outer functions return address so the inner function can return there.

in C there are 3 import memory areas:

- static

- heap

- stack

mips divides registers into 2 categories:

- Preserved across function call ($ra, $sp, $gp, $ , “saved registers” $s0-$s7)

- Not preserved ($v0, $v1), argument registers $a0-$a3, temp $t0-$t9

c has 2 storage classes:

automatic: variables are local to function and discarded staic: variables exist across exits from and entries to procedures

use stack for automatic (local) variables that dont fit registers

procedure frame or activation record: segment of stack with saved registers and local variables.

L7

C has 2 storage classes: automatic and static

- Automatic: variables are local to function and discared when function exits

- Static: vairables exist across exits from and entries to procedures

use stack for automatic (local) variables taht dont fit in registers

procedure frame or activation record: segment of stack with saved registers and local variables

some mips compilers use a frame pointer ($fp) to point to first word of frame.

$gp: global pointer points to start of static data.

heap: dynamic data, grows and shrinks depending on when you allocate and free memory.

26 and 27 used by the operating system.

register 1 is used by assembler.

stored-program computer

- instructions are represented as bit patterns - can think of these as numbers

- therfore, entire programs can be stored in memory to be read or written just like data.

- can reprogram quickly (seconds), dont have to rewire computer (days)

- know as the “von neumann” computers after widely distributed tech remort on EDVAC project

Everything addressed

- since all instructions are stored in memory everything has a memory address: instructions, data words

- c pointers are just memory addresses: they can point to anything in memory

- one register keeps address of instruction being executed: “Program Counter” (PC)

L8

MARS - mips simulator, allows you to run mips code on x86 or other architecture machine.

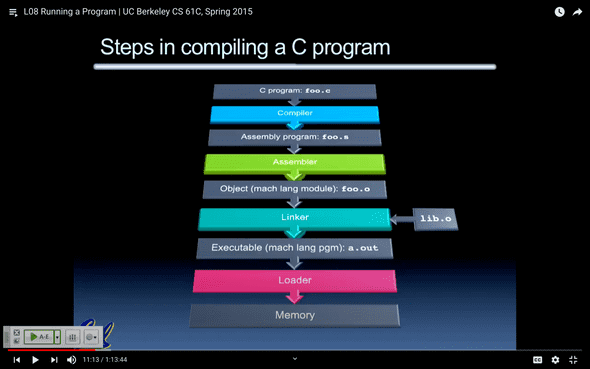

Running a program (compiling, assembling, linking, loading)

Interpreter: program that executes other programs.

Language translation gives us another option.

In general we interpret a high level language when efficiency is not critical and translate to a lower-level language to up performance.

interpreter executes program in the source langauge

translator converts a program from source language to an equivalent program in another langauge

example of interpreted language: python, javascript

Can be useful to interpret machine language for learning/debuging.

Translated/compiled code almost always more efficient.

compiler takes high level code and returns assembly

assembler turns assembly code to object code

multiplication: 32 bit * 32 bit = 64 bit value (in mips)

mult register1, register2

puts result in special result register

puts upper half in hi, lower half in lo

hi and lo are 2 registers separate from 32 general purpose registers.

use mfhi register and mflo register to move from hi, lo

C code

a = b * cmips code

mult $s2, $s3

mfhi $s0

mflo $s1division:

div register1, register2

C code

a = c / d;mips code

div $s2, $s3

mflo $s0

mfhi $s1assembler goes through assembly code twice, first to get labels, second to setup code

HW 1

https://github.com/BrooksPoltl/cs61c/tree/master/hw1

HW 2

https://github.com/BrooksPoltl/cs61c/tree/master/hw2

READINGS

2.1 Introduction

instruction sets are very similar to each other. Similar to SQL in that if you learn one instruction set it is very easy to pick up another.

computer designers are focused on writing instruction sets that are easy as well as cost and energy efficient.

stored-program concept: many data types can be stored as a number.

2.2 Operations of the Computer Hardware

Every computer must be able to perform arithmetic. You can chain aritmetic operations for example since add is stored to a variable you can set that variable again with the sum of the previous operation plus the next value.

Design principle 1: simplicity favors regularity.

Java compilation done later than C compilation (just in time compilation or JIT). s

2.3 Operands of the Computer Hardware

Operands are limited in instructions, they must be a part of the register which is 32 bits also known as a “word”. There are 32 32 bit registers.

Design principle 2: smaller is faster.

The farther electronic symbols have to travel the longer it takes.

There is also a need to move data from registers to memory, these are called data transfer instructions. Memory is just a large sigle dimensional array with the address being the index.

Words must start at addresses that are multiples of 4. This is common and called an alignment restriction.

Many programs use more variables than there are registers so more frequently used variables are stored in registers and less frequent are stored in memory. This is called “spilling registers”.

2.5 Representing Instructions in the Computer

Format for instructions in decimal:

add $t0, $s1, $s2

#decimal

0 | 17 | 18 | 8 | 0 | 32

#binary

000000 | 10001 | 10010 | 01000 | 00000 | 100000the left and right indicate the instruction to perform.

Notice that the left and right are both 6 bits instead of 5. The sum of all of these bits is 32 to represent the size of a single word. Each one of these columns in a single row represents a “field”. The second and third field represents the operands which are $s1 and $s2 respectively. The fourth represents the register that receives the output. The fifth is unused here which is why it is set to 0.

To distinguish from assembly the numeric representation of the instruction is called “machine language”.

Hexadecimal is very easy to convert to binary. Since hexadecimal is base 16 and binary is base 2. You convert by grouping together 4 bits and converting it to its hexadecimal equivalent.

11100001 = E1

1110 = E # first four

0001 = 1 # last fourC and Java use 0xnnnn notation for hexadecimal.

Further breakdown of instructions:

# register format or r-type or r-format

op | rs | rt | rd | shamt | funct

# op: Basic operation of the instruction aka opcode.

# rs: first register source operand

# rt: second register source operand

# rd: register destination operand

# shamt: shift amount

# funct: function or function code, selects the specific variant of the operation in the op fieldIdealy we would like to keep all instructions the same size, but some require more than 32 bits given the above format like lw (load word) since it includes constants.

Design Principle 3: Good Design demands good compromises.

This issue with constants has led us to the next instruction format:

# immediate format or i-type or i-format

# op, rs and rt remain the same size of bits.

op | rs | rt | constant or address (16 bits)in a load word instruction the rt meaning changes to the destination field.

2.6 Logical Operators

A shift moves all of the bits in a word to the left or right leaving 0 in its place. These are sll and srl in mips (shift left logical and shift right logical).

There is also AND, OR, NOT, and NOR.

2.7 Instructions for Making Decisions

beq and bne (branch equal and branch not equal) goes to a statement if something is true. These are conditional branches there are also unconditional branches like jump, which will jump to a certain statement no matter what.

Most programming languages have a case/switch statement. This requires a jump address table to jump to whichever instructions are true.

2.8 Supporting Procedures in Computer Hardware

A procedure has 6 steps:

- Put parameters in a place where the procedure can access them.

- Transfer control to the procedure.

- Acquire the storage resources needed for the procedure.

- Perform the desired task.

- Put the result value in a place where calling the program can access it.

- Return control to the point of origin, since a procedure can be called from several points in a program.

Registers are fastest place to hold data. There are 4 argument registers a0-a3, 2 value registers to return v0-v1, and 1 return address (ra). For procedures there is a specific instruction jal (jump and link) this jumps to the address and saves it in the return address.

2.9 Communicating with People

Computers originally created for numbers, but when they were commercially viably there was a need to be able to process text. Computers today offer an 8 bit byte to represet characters with the American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) being the standard.

Characters are normally combined into strings.

There are 3 choices for string representation:

- The first position is reserved to indicate length

- An accompanying variable has the length

- The last position of the string indicates the length

Unicode is a unversal encoding of the alphabets of most human langauges. Unicode uses 16 bits.

2.12 Translating and Starting a Program

Compiler

The compiler transforms the C program into an assembly language program. Compiling is good because it allows the programmer to write programs in less lines of code. This also makes it easier to understand for humans.

Compilers use to be inefficient so some low level stuff was writter in assembly, but now compilers can output optimized code nearly as well as assembly experts.

Assembler

Assembler takes assembly code and turns it into machine code. The assembler outputs an object file that consist of language instructions, data, and information needed to place instructions properly into memory.

To produce binary, the assembler must determine the address corresponding to the labels, assemblers do this by using a symbol table. Which is an object containing a key value pair of addresses and symbols.

Object file usually contains 6 things:

- object file header giving the size and position of stuff

- the text segment contains the machine language code

- the static data segment contains data allocated to life of program.

- relocation information identifies instructions and data words that depend on absolute addresses

- symbol table containing previously mentioned key value store

- debugging information contains information regarding compilation

Linker

Linkers allow you to not have to recompile everything when a line changes within the application.

Also known as a link editor. It contains things at a procedure level so it only has to recompile the procedures that are changed.

Steps for linking:

- Place code and data modules symbolically in memory.

- Determine the addresses of data and instruction labels.

- Patch both the internal and external references.

The linker produces an executable file that can be run on the computer.

Loader

Loader in UNIX follows these steps:

- Reads the executable file header to determine size of the text and data segments

- Creates an address space large enough for the text and data

- Copies the instructions and data from the executable file into memory

- Copies the parameters (if any) to the main program onto the stack

- Initializes the machine registers and sets the stack pointer to the first free location.

Dynamically Linked Libraries

Library routines are not linked and loaded until the program is run. In initial implementations the loader ran a dynamic linker for libraries. Using the file to find library references.

Java Virtual Machine

Java code is compiled down to java bytecode instruction set. This byte code is used by the interpreter called the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). An interpreter is a program that simulates an instruction set architecture.

The downside with interpreters is the hits to performance. To combat this Java development allowed for compilers to translate while the program was running. This is known as “Just in Time compilers” (JIT).